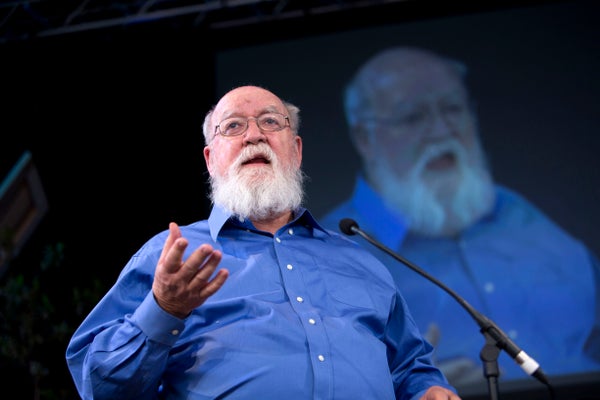

Philosopher Daniel Dennett died a few days ago, on April 19. When he argued that we overrate consciousness, he demonstrated, paradoxically, how conscious he was, and he made his audience more conscious.

Dennett’s death feels like the end of an era, the era of ultramaterialist, ultra-Darwinian, swaggering, know-it-all scientism. Who’s left, Richard Dawkins? Dennett wasn’t as smart as he thought he was, I liked to say, because no one is. He lacked the self-doubt gene, but he forced me to doubt myself. He made me rethink what I think, and what more can you ask of a philosopher? I first encountered Dennett’s in-your-face brilliance in 1981 when I read The Mind’s I, a collection of essays he co-edited. And his name popped up at a consciousness shindig I attended earlier this month.

To honor Dennett, I’m posting a revision of my 2017 critique of his claim that consciousness is an “illusion.” I’m also coining a phrase, “the Dennett paradox,”which is explained below.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Of all the odd notions to emerge from debates over consciousness, the oddest is that it doesn’t exist, at least not in the way we think it does. It is an illusion, like “Santa Claus” or “American democracy.”

René Descartes said consciousness is the one undeniable fact of our existence, and I find it hard to disagree. I’m conscious right now, as I type this sentence, and you are presumably conscious as you read it (although I can’t be absolutely sure).

The idea that consciousness isn’t real has always struck me as absurd, but smart people espouse it. One of the smartest is philosopher Daniel Dennett, who has been questioning consciousness for decades, notably in his 1991 bestseller Consciousness Explained.

I’ve always thought I must be missing something in Dennett’s argument, so I hoped his 2017 book From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds would enlighten me. It does but not in the way Dennett intended.

Dennett restates his claim that Darwinian theory can account for all aspects of our existence. We don’t need an intelligent designer, or “skyhook,” to explain how eyes, hands and minds came to be because evolution provides “cranes” for constructing all biological phenomena.

Natural selection yields what Dennett calls “competence without comprehension.” (Daniel Dennett loves alliteration.) Even the simplest bacterium is a marvelous machine, extracting from its environment what it needs to survive and reproduce. Eventually, the mindless, aimless process of evolution produced Homo sapiens, a species capable of competence and comprehension.

But human cognition, Dennett emphasizes, still consists mainly of competence without comprehension. Our conscious thoughts represent a minute fraction of all the information processing carried out by our brain. Natural selection designed our brain to provide us with thoughts on a “need to know” basis, so we’re not overwhelmed with data.

Dennett compares consciousness to the user interface of a computer. The contents of our awareness, he asserts, bear the same relation to our brain that the little folders and other icons on the screen of a computer bear to its underlying circuitry and software. Our perceptions, memories and emotions are grossly simplified, cartoonish representations of hidden, hideously complex computations.

None of this is novel or controversial. Dennett is just reiterating, in his oh-so-clever, neologorrheic fashion, what mind scientists and most educated layfolk have long accepted: that the bulk of cognition happens beneath the surface of awareness. Dennett even thanks the much-vilified Sigmund Freud for his “championing of unconscious motivations”!

Trouble arises when Dennett, extending the computer interface analogy, calls consciousness a “user-illusion.” I italicize “illusion” because so much confusion flows from Dennett’s use of that term. An illusion is a false perception. Our thoughts are imperfect representations of our brain/mind and of the world, but that doesn’t make them necessarily false.

Take this thought: “Donald Trump is a narcissistic jerk.” That is an extremely compressed statement about an extremely messy external reality. Moreover, my ability to think the thought, or type it on my laptop, depends on complex hardware and software, the workings of which I am happily ignorant. But that doesn’t mean “Donald Trump is a narcissistic jerk” is an illusion any more than “2 + 2 = 4.”

What if I think, “2 + 2 = 5,” “Global warming is a hoax” or “Donald Trump is the wisest man on Earth”? What if I have a psychotic disorder or am living in a simulation created by evil robots, and all of my thoughts are illusions? To say my consciousness is therefore an illusion would be to conflate consciousness with its contents. That’s like saying a book doesn’t exist if it depicts nonexistent things. And yet that is what Dennett seems to suggest.

Consider how Dennett talks about qualia, philosophers’ term for subjective experiences. My qualia at this moment are the smell of coffee, the sound of a truck rumbling by on the street, my puzzlement over Dennett’s ideas. Dennett notes that we often overrate the objective accuracy and causal power of our qualia. That is true enough.

But he concludes, bizarrely, that therefore qualia are fictions, “an artifact of bad theorizing.” If we lack qualia, then we are “zombies,” creatures that look and even behave like humans but have no inner, subjective life. Imagining a reader who insists he is not a zombie, Dennett writes:

The only support for that conviction [that you are not a zombie] is the vehemence of the conviction itself, and as soon as you allow the theoretical possibility that there could be zombies, you have to give up your papal authority about your own nonzombiehood.

Think you’re conscious? Think again.

Dennett gets annoyed when critics accuse him of saying “consciousness doesn’t exist.”And to be fair, he never flatly makes that claim. Rather his point seems to be that consciousness is so insignificant, especially compared to our exalted notions of it, that it might as well not exist.

When I encounter a baffling belief, at some point I stop trying to understand the belief and focus on the believer. What’s the motive? Why would Dennett expend so much energy advancing such a preposterous position?

Like many philosophers, Dennett clearly gets a kick out of defending positions that defy common sense. But his primary agenda is defending science against religion and other irrational belief systems. Dennett, an outspoken atheist, fears that creationism and other superstitious nonsense will persist as long as mysteries do. He thus insists that science can untangle even the knottiest conundrums, including the origin of life (which he asserts that recent “breakthroughs” are helping to solve) and consciousness.

Dennett accuses those who question science’s power of bad faith; these doubters don’t want their “beloved mysteries” explained. Dennett can’t accept that anyone might have legitimate, rational reasons for resisting his reductionist vision.

Some people surely have an unhealthy attachment to mysteries, but Dennett has an unhealthy aversion to them, which compels him to stake out unsound positions. His belief that consciousness is an illusion is wackier than the belief that God is real. Science has real enemies—some in positions of great power—but Dennett doesn’t do science any favors by shilling for it so aggressively.

Let me nonetheless conclude by thanking Dennett. Agree with him or not, I always find him provocative and entertaining. And when he argues, passionately, brilliantly, against consciousness, he not only demonstrates how hyperconscious he is; he also rouses the rest of us from our zombielike torpor and makes us more conscious. Call it the Dennett paradox.

A version of this updated article appeared at johnhorgan.org.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.