Nearly 40 percent of U.S. homes have gas stoves, which spew a host of compounds that are harmful to breathe, such as carbon monoxide, particulate matter, benzenes and high quantities of nitrogen dioxide.

Decades of well-established research have linked nitrogen dioxide, or NO2, to respiratory conditions such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which especially affect children and older adults. This harmful link is so well established that some states have begun banning gas appliances in new construction. And now a new study has shown in stark detail just how long and far this gas spreads and lingers in a home. By sampling homes across the U.S., the researchers found that in many, levels of exposure to NO2 can soar above the World Health Organization’s one-hour exposure limit for multiple hours—even in the bedroom that is farthest from the kitchen.

"The concentrations [of NO2] we measured from stoves led to dangerous levels down the hall in bedrooms ... and they stayed elevated for hours at a time. That was the biggest surprise for me," says Rob Jackson, a sustainability researcher at Stanford University and senior author of the study, which was published on May 3 in Science Advances.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

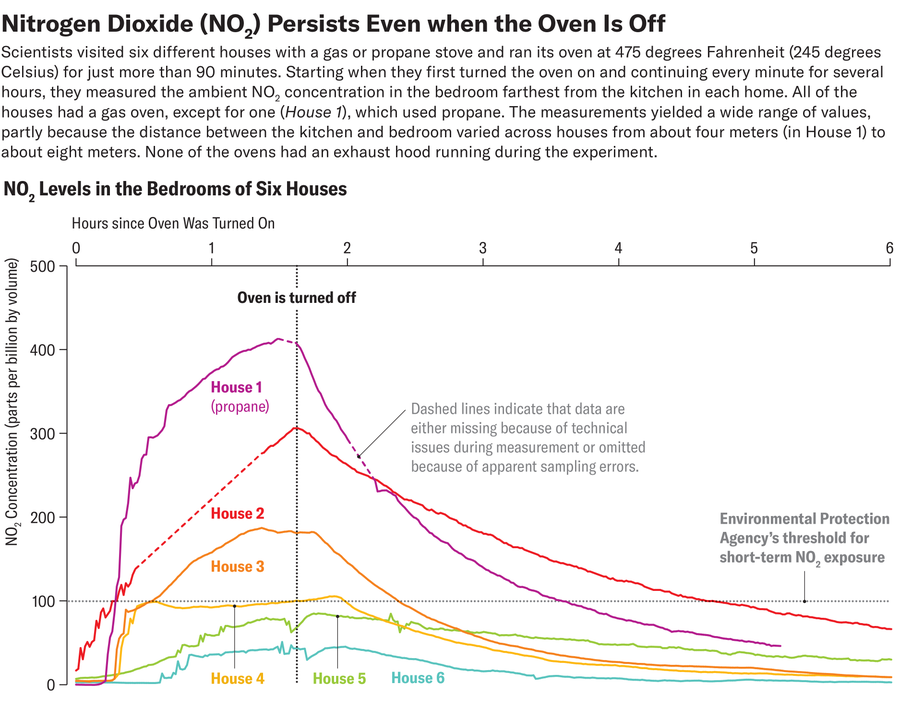

The researchers collected real-world data on NO2 concentrations before, during and for several hours after the use of gas and propane stoves in houses and apartments in California, Colorado, Texas, New York State and Washington, D.C. In six homes, they tested the levels of NO2 in the bedroom farthest from the kitchen for a basic “bread baking” scenario: they set the gas or propane oven to 475 degrees Fahrenheit (245 degrees Celsius) and left it on for an hour and a half. The team continued sampling the air for up to six hours after the oven was turned off.

In all six homes, the NO2 concentration in the bedroom quickly exceeded the WHO’s chronic exposure guideline of about five parts per billion by volume. And in three of the bedrooms, the levels soared even above the Environmental Protection Agency’s and the WHO’s respective one-hour exposure guidelines, which both set the limit at about 100 parts per billion by volume. (The EPA’s guidelines are intended for outdoor air exposure because the agency does not regulate indoor air pollution.)

The bedroom exposure data from the new study can be seen in the graph above. “Think about that graph happening two times a day," Jackson says. “You cook at lunch, and then you cook again at dinner. Maybe you cook breakfast. It’s over and over again, hundreds of days a year.”

Jackson and his colleagues next wanted to find out which factors had the greatest impact on the level of NO2 exposure from gas stoves. So they used a computer model to estimate airflow and contaminant concentration in indoor spaces. They validated the model by comparing its estimates with directly measured concentrations of NO2 from 18 homes of differing sizes and layouts before, during and after using a gas stove. The researchers tested this with the range hood on and off and with the kitchen windows open and closed, airing out the residences between each trial.

After confirming that their real-world observations matched the model’s predictions, the team could then use the program to estimate how much NO2 someone might be exposed to depending on many different factors, such as their home’s size and layout, the amount of time they spend with the windows open and how often they use the stove’s range hood.

The researchers found that those living in homes smaller than 800 square feet or making under $35,000 a year were being regularly exposed to levels of NO2 at or far exceeding the WHO’s threshold for chronic exposure. Finally, by combining these data with previous research on the link between long-term gas and propane stove exposure and pediatric asthma, the researchers calculated that such exposure could account for 200,000 current cases of childhood asthma, with 50,000 of those attributable to NO2 alone.

"I think that this modeled data is valuable because it gives you very clear numbers” to see how much NO2 we’re being exposed to at different time points during and following gas stove use, says pulmonologist Laura Paulin, who studies indoor air pollution at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. “We are blowing past these outdoor air regulations [and] recommendations” with indoor NO2 exposure alone, she says.

In a 2014 study, Paulin and her colleagues showed how people can decrease concentrations of this pollutant in their home. The best way is to swap out a gas or propane stove for an electric one. But for some people, especially renters, this may not be a feasible option.

If you’re stuck with a gas stove, Paulin suggests turning on your range hood every time you cook with gas, even if the fan is loud and annoying. Still, these aren’t always very effective: Jackson and his colleagues found that the hoods in the homes they surveyed were anywhere between 10 and 70 percent effective. Those numbers applied only to hoods that vented outside. Some hoods instead spew air right back into your living space and do little more than disperse the pollutants throughout it.

Another way to improve ventilation is to open your windows while you cook—if weather permits and if the outside air is not polluted as well.

And if all else fails, high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) air purifiers can help filter out some of these indoor pollutants. If the purifier has a carbon prefilter, it can remove some NO2 from the air. In Paulin’s 2014 study, she found that placing such filters in the kitchen could reduce NO2 levels by 20 percent.

As we spend more of our lives indoors, it becomes increasingly important to pay attention to the quality of the indoor air we breathe. “Our outdoor air is getting cleaner. But we have ignored indoor air pollution in considering risk for people in this country,” Jackson says.