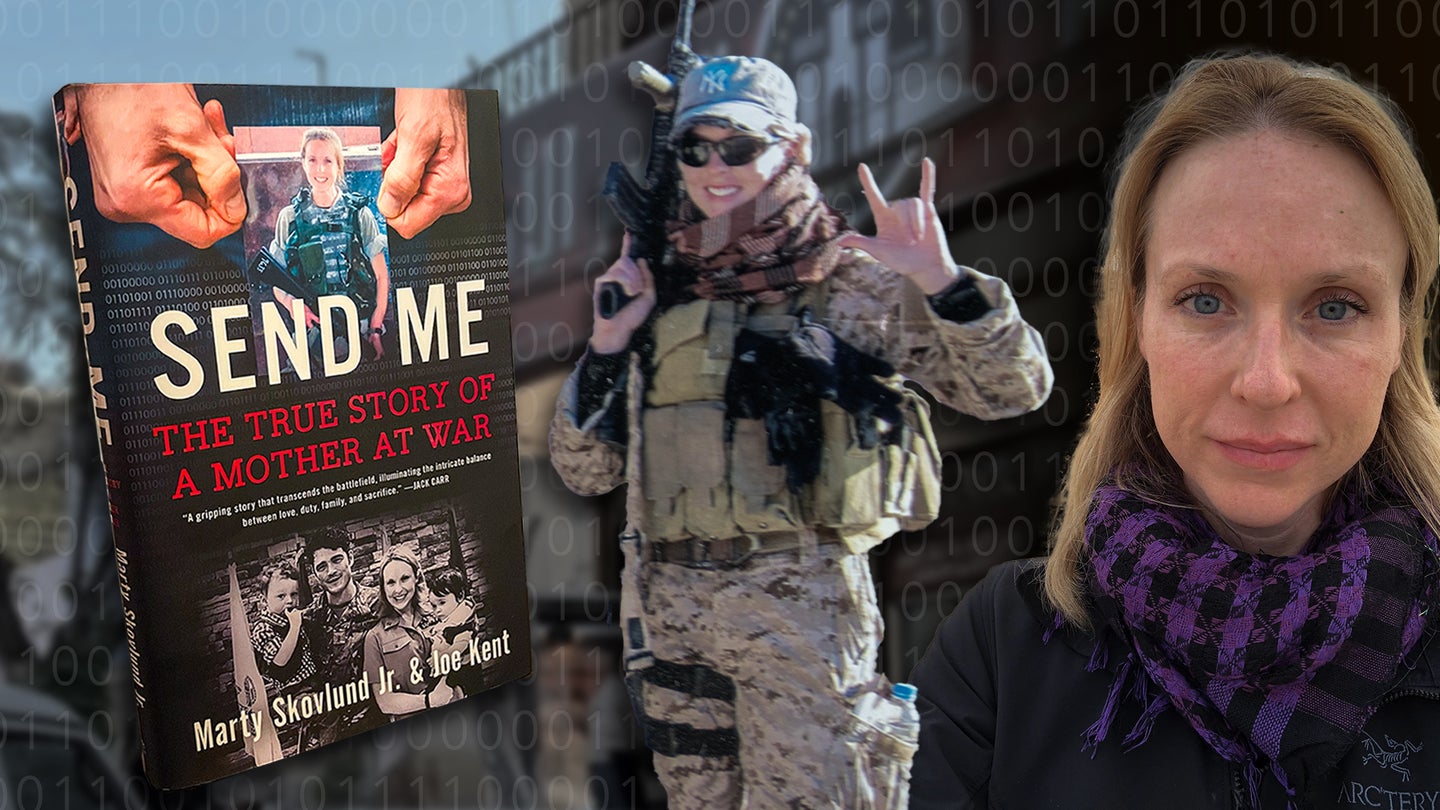

‘Send Me’: Senior chief Shannon Kent and the hunt for ISIS

This excerpt from the forthcoming “Send Me: The True Story of a Mother at War,” follows Navy chief Shannon Kent's hunt for a senior ISIS leader.

This is an excerpt from the forthcoming book “Send Me: The True Story of a Mother at War,” a biography of Navy Senior Chief Shannon Kent written by her husband Joe Kent, and Task & Purpose editor-in-chief Marty Skovlund, Jr. A specialist in cryptologic warfare and fluent in seven languages, Kent was the first woman to complete the Naval Special Warfare Direct Support Course and the first to operate with Naval Special Warfare units in direct combat. She was killed in a targeted bombing in Syria on Jan. 16, 2019. This excerpt has been condensed from its original version.

A black Hyundai Elantra, covered in dust and sporting a few dents, cruised down a two-lane highway in the Syrian desert against the backdrop of a beautiful sunrise. Red in the morning, sailors take warning, Kay thought, sitting in the backseat. They didn’t use real names on missions, but you still needed something easy to remember. “Kay” was easy enough.

The radio dial was stuck on Al-Madina FM, a manageable but annoying situation Kay and the other two operators dealt with on their ninety-minute morning drive. It was too early for nonstop Arabic music, but conversation died down about an hour ago, so it is what it is.

The mission was to meet a source at a small compound in the middle of nowhere. It was a potentially dangerous rendezvous. Air support would be nice, in case things went south, but you’re in the wrong line of work if you expect that kind of safety net.

This meeting wasn’t their first rodeo, and if anyone knew how to navigate it successfully, it was these three. They had a combined fifty years of military experience, almost all of it in special operations. They were all selected and trained for their ability to hunt humans off the grid, in ambiguous situations, with little to no support. They were entirely in their element.

They weren’t wearing body armor or helmets—hell, they weren’t even wearing uniforms—unless you count the faded New York Yankees ball cap Kay always had on. No machine guns or rocket launchers, just a Glock in the waistband and one spare magazine.

Two of the three looked how most would picture a stereotypical operator on a low-visibility mission: tan skin, longish hair, and beards. Kay opted for a ponytail.

The driver was a native-born Iraqi who came to the United States after his parents fled Saddam Hussein–controlled Iraq during the 1990s and went by the call sign “Jake,” but only because “Jake from State Farm” was too long for a radio transmission during a firefight.

Scotty rode shotgun. An old frogman-turned-contractor, he wore a pair of Oakleys, a black Casio G-Shock watch wrapped around his tattoo-laden arm, and a well-worn Black House MMA T-shirt from Brazil. He was Kay’s lookout during meets.

Seventy thousand of the 1.3 million active-duty service members in the US military are assigned to the US Special Operations Command (USSOCOM). Among them are the operators—the one percent of the one percent.

But few realize these same operators are the friendly neighbors and Little League coaches back home, tasked with balancing home and work like any other busy American. Well, almost like any other American.

Shit, I forgot to check in with Joe to see how Colt’s doctor’s appointment went today, Kay thought. Long drives like this allowed these hardened operators to get lost in their thoughts about the world back home. War or not, the kids needed to be taken care of, and marriages must be maintained. It’s a delicate balancing act.

“We’re about ten minutes out,” Jake said, breaking the silence in the car. Kay sat up a little straighter and began mentally preparing for the looming prospect of violence that could occur if the source decided their loyalty to the coalition had a limit. Typically, it’s all chai and smiles and empty promises—but bloodshed was always possible.

“Let’s do a first pass to check out the compound,” Kay said. “I don’t want to roll in there until we’ve had a chance to get eyes on.”

“Sounds good,” Jake replied before spitting tobacco juice into an empty energy drink can he had wedged between his legs. One dirty secret of the war on terror: it was fueled by chewing tobacco and energy drinks. Or, in Kay’s case, Rothman cigarettes—but only because she couldn’t find her preferred Marlboro Smooths while deployed.

After driving approximately one hundred meters past the compound, Jake performed a U-turn and headed back. He pulled over outside the gate, allowing Kay and Scotty to exit and walk into the compound’s courtyard. He kept the car running.

The two approached the main building, and a man—a sheikh— emerged, dressed in traditional Arabic clothing with an orange kaffiyeh wrapped around his head.

“MarHaban, as-salaam‘alaykum.” Kay delivered the standard Arabic greeting with a perfect accent for the region, immediately recognizing him as the source they were there to meet.

“Wa ‘alaykum salaam,” the man replied while placing his right hand on his chest. So far, so good, Chief Petty Officer Shannon Kent—“Kay”—thought. Scotty stood nearby, his eyes darting from the Sheikh to the young man with an AK-47, then back again.

Then, in perfect English, the Sheikh said, “I did not expect a woman.”

A mission waits on Shannon

Several miles away, thirty American commandos prepared for close combat in a large canvas tent—the “ready room”—filled with wooden cubbies that stored their tools of war. The operators had already double-checked the explosive charges they built for breaching gates and doors, carefully removed the safeties from their grenades, and performed function checks on everything from their heavy machine guns to sniper rifles to their medical gear. Their lives depended on it.

Outside their tent, specialized helicopters stood fueled on the tarmac. Everyone was waiting on the green light to board those helicopters and a chance to kill or capture Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS. Al-Baghdadi was the most elusive and dangerous member of the militant extremist’s cadre, responsible for an organized campaign of terror that swept across the Middle East, resulting in tens of thousands dead, thousands enslaved, and providing inspiration for brutal terrorist attacks across the Western world.

To board the helicopters and launch the raid, they needed to know where Al-Bagdadi was. With someone like al-Baghdadi, every second counted. But the commandos were helpless until the information about his whereabouts came in, stuck on the airfield in a state of bored readiness.

Everything depended on Shannon.

Find, Fix, Finish

Shannon replied to the Sheikh in Syrian Slang, “America ba’tat ashaukhos el wassqeen fee, em-Shan yalt’ie bil ashkass el wassqeen fee hoon.” (“America sent the one they trust to meet the one they trust.”)

This mission wasn’t the first time she had to respond to men surprised by a female operator. Her confidence and knowledge of local languages and customs helped her through countless times over the previous fifteen years; her linguistic ability and guile were as much of a weapon as the Glock concealed beneath her shirt.

Shannon’s role as an operator was to find and fix terrorists like al-Baghdadi and his ilk in time and space. These are the first two steps in the Find, Fix, Finish, Exploit, Analyze, Disseminate (F3EAD) targeting methodology America’s special operators use to dismantle enemy networks.

The magnitude of her mission was not lost on her. The pressure from the shooters to “paint the X on this motherfucker” was a heavy weight, and the information she needed to obtain would send her brothers toward violence. She was their eyes and ears, right up to the point they encountered the enemy in person.

A surprised smile spread across the Sheikh’s face as he studied the woman in front of him. She looked American—like a woman out of an action movie—dressed in dark gray prAna pants, a black Arc’teryx jacket, and a purple Syrian kaffiyeh around her neck, yet she spoke with a native Syrian accent. America had sent her and just two men. This is different, he thought.

“Tafadil.” The Sheikh welcomed her with an extended hand. They shook hands—Syrians are far from being strict Muslims who refuse to touch women they are not related to

The familiar sounds of a scampering toddler filled the courtyard of the Sheikh’s house. “Ali Abdullah, come here!” his mother called after him.

This guy is probably not going to risk killing us with his family here, she thought

The Sheikh motioned to a seat on the couch to the right of his desk.

Shannon turned her attention to the reason they just risked a drive through the Euphrates Valley no-man’s-land: the source. He was a key tribal Sheikh with a long history with ISIS, the Assad regime, the Kurds, and every other power broker in the region. He was the key to finding, fixing, and hopefully finishing al-Baghdadi.

Shannon did her homework on him for weeks before the meeting, poring over intelligence reports about the tribe and the Sheikh himself. She was not surprised to see the classified information on him was lacking compared to what he put out on social media. And to think, we used to have to steal this shit. Now everyone posts everything about their lives online, free for the taking, she thought.

“Thank you so much for meeting with me today and inviting me into your home,” Shannon said. “My colleagues and I were sent here to thank you for your efforts against Daesh on behalf of the US government.” Her initial assessment of the source started here, even if her opening line was seemingly benign.

She had referred to ISIS as Daesh, a derogatory word in Arabic for ISIS, which ISIS itself despises. The term takes ISIS’s Arabic name and turns it into an American-style acronym (al-Dawla al-Islamiya fi al-Iraq wa al-Sham). They hate this term because it literally translates to “bigotry” and is also a feminine verb. Casually throwing the word Daesh into a compliment was a surefire way to gauge his feelings about ISIS.

Without warning, the telltale report of an AK-47 burst ripped through the air, echoing through the room from outside the building. Shannon’s hand instinctively moved to her pistol; the Sheikh was visibly confused. Scotty had already moved out, leaving Shannon alone. She had seconds to consider what to do.

Excerpted from “Send Me: The True Story of a Mother at War” by Marty Skovlund Jr. and Joe Kent, to be published May 7 by William Morrow. Copyright © 2024 by Joe Kent and Marty Skovlund Jr. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers.

The latest on Task & Purpose

- Army captain gives up his rank to enlist in the Marine Corps

- Army fires commander of Germany-based air defense unit

- Navy offers some sailors $100,000 to reenlist

- Army general bans most work texts after duty day

- Air National Guard officer and state senator arrested for burglary